2012-11-08

Demand for Right Wing Extremism in Poland

Right wing extremism is on the rise in Europe, yet for a long time social scientists appeared to be lacking the appropriate tools for an assessment of its pervasiveness and of the threat it potentially poses to democratic political institutions. In order to fill this void, The Political Capital Institute carried out a series of analyses of European Social Survey (ESS) data from over thirty countries collected throughout the five waves of the study – in 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, and 2010 – and introduced a new variable for exploring the demand for extreme right-wing ideas within different European societies, namely the Demand for Right-Wing Extremism (DEREX) index.

DEREX consists of four components:

- Prejudice and welfare chauvinism, comprising such factors as anti-immigrant and anti-minority (including sexual minorities) attitudes, support for restrictive immigration policies, etc.;

- Anti-establishment attitudes based on a lack of trust in the authorities, in democratic institutions (both national and international), in the judicial system and in the police, and a general dissatisfaction with the political system;

- Right-wing value orientation, consisting of a strong need for social order and obedience, adhering to traditional values, religiosity and political self-definition as a right-wing supporter;

- Fear, distrust and pessimism connected with a general dissatisfaction with one’s life and economic situation, distrust of other people and insecurity.

DEREX identifies the proportion of people in each of the surveyed countries that scores very high in at least three of the four dimensions mentioned above. Thus it provides an idea of the size of the group most susceptible to extreme right-wing rhetoric.

DEREX in Poland (2003-2011)

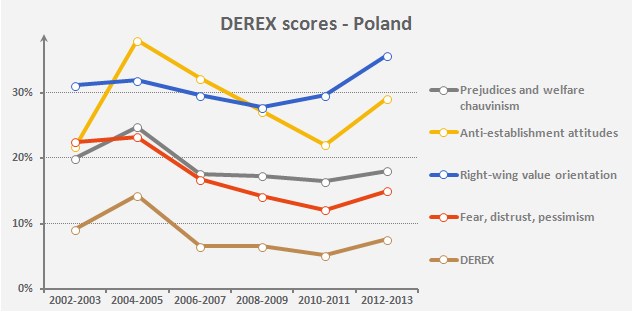

According to the most recent ESS results, Poland’s DEREX index is currently at a level of 5% (meaning that 1 in 20 Poles is prone to support the extreme right), placing the country on the 15th spot among the 26 countries surveyed in 2010. The longitudinal character of the ESS allows for a scrutiny of temporal changes in the Polish DEREX scores. In 2003, around 10% of Polish people constituted the potential base for right-wing politics and by 2005 this proportion had risen quite substantially reaching almost 15%. Since 2007, however, an opposite trend can be observed, namely a significant reduction in DEREX scores which fell to around 5-6%.

An analysis of Poland’s scores on the dimensions included in DEREX as well as the index itself throughout the five waves of ESS (See Fig. 1), yields some interesting corollaries regarding the interplay between them and the social, political and economic situation of the country. Three of the four categories display remarkable dynamics while only one of them, that is the adherence to right-wing values, is quite stable in Polish society with about 30% almost constantly declaring themselves as supporters of these values.

Figure 1. DEREX scores in Poland (ESS5). Source: Political Capital Institute.

DEREX and the changing political situation

DEREX scores turn out to likely be heavily influenced by political tensions. The highest Polish scores observed can be at least partially explained by the economic and political crises of 2001-2002 and 2005. The first one happened during the time of a noticeable downturn in the Polish and global economy. A general worsening of the economic situation, due to increased unemployment, led to a spike in relative deprivation in Poland. The term relative deprivation, elaborated since the mid-20th Century, either refers to the perception of a person that they deserve some goods, which they do not possess, in combination with the knowledge that other people are in possession of them (individual relative deprivation) or that their respective group is in a worse situation than other groups (group relative deprivation). Pettigrew et. al. (2008) convincingly argued that relative deprivation – especially the one at the group level – is significantly correlated with prejudice. This could serve as an explanation why the level of prejudice was quite high at the beginning of the 2000s.

What is more, the intense political crisis of 2005, when the leftist ruling party lost power after a series of corruption scandals, was probably reason enough to account for the rapid increase in anti-establishment attitudes at the time. Ever since the general election of 2007, the political and economic situation in Poland has been relatively stable and therefore DEREX exhibits lower levels during that time.

Conclusion

Three of the four components of DEREX (prejudice, anti-establishment attitudes and fear, distrust and pessimism) seem to be quite heavily influenced by situational factors, but the fourth one, namely the right-wing value orientation, is more of a stable, personal characteristic. The definition of the latter category draws heavily from concepts of authoritarian personality (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford, 1950) and right-wing authoritarianism (Altemeyer, 1981) both of which assume that adherence to extreme right-wing ideology is a consequence of particular personality traits. Altemeyer proposed that authoritarians are characterised by a need for submission to authorities, by specific authoritarian aggression (directed mostly at groups that happen to deviate from the generally perceived social order, such as sexual minorities and immigrants) and conventionalism, i.e. a very strong adherence to social norms.

The fact that the proportion of Polish society supporting right-wing values is quite large and steadily so and that the other three dimensions of the demand for right-wing extremism are to a great extent shaped by the political context may be seen as cause for concern. That is especially true, if one takes into account that economic forecasts for the nearest future are generally rather bleak in which case an increase in right-wing support is likely to occur.

Mikołaj Winiewski, Anna Stefaniak

REFERENCES: Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York: Harper and Row. Altemeyer, B. (1981) Right-wing authoritarianism. University of Manitoba Press.